Clarifying Board Roles: Emerging Best Practices in System vs. Subsidiary Board Duties

Last winter, I facilitated a Governance Institute educational session with hospital board members entitled “Board Basics for Effective Governance.” Expecting most participants to be relatively new board members, I was surprised to find that most of the session’s attendees had served on hospital boards for five or more years. When I asked the group about their most pressing questions related to hospital governance, participants indicated that they were most unclear about the appropriate roles for their boards to play now that their hospital had joined a larger regional or national health system. This article seeks to address such “role confusion” by focusing on emerging best practices in the balance of board roles between system boards and subsidiary boards.

Three Primary Roles of Independent Hospital Boards

Historically, independent hospital boards performed three primary roles:

- Approve mission and set strategic direction. An independent hospital board approves the organization’s mission and sets strategic direction, including a vision for the future and key goals to achieve the organization’s vision and realization of its mission. The board should also approve goal-related metrics to measure progress toward achieving its goals.

- Set policy. In independent hospitals, boards establish policies for the organization’s performance. These may include financial, quality, operational, and HR policies. Typically, hospital boards maintain committees such as finance, quality, governance, and compliance to inform the policy discussions of the board and to ensure that appropriate performance targets are established. Such policy-setting is also informed by the expertise of the senior leadership team and industry knowledge.

- Provide oversight. Independent hospital boards oversee the organization’s performance. If performance is not satisfactory, boards ask management for a corrective action plan and monitor ongoing performance to ensure that the hospital gets back on track. Additionally, the board selects and reviews the hospital’s CEO, establishes CEO performance expectations, and adopts a CEO compensation philosophy and plan.

The Shift from Independent Hospital to System Subsidiary

With nearly two-thirds of community hospitals now participating in larger healthcare systems, hospital board members need to play very different roles than they have historically. Having grown up as a board member for an independent hospital, where the board was the final decision authority, this shift in roles can cause confusion, duplication of efforts, and/or frustration on the part of local board members who feel that they no longer are playing a truly fiduciary role.

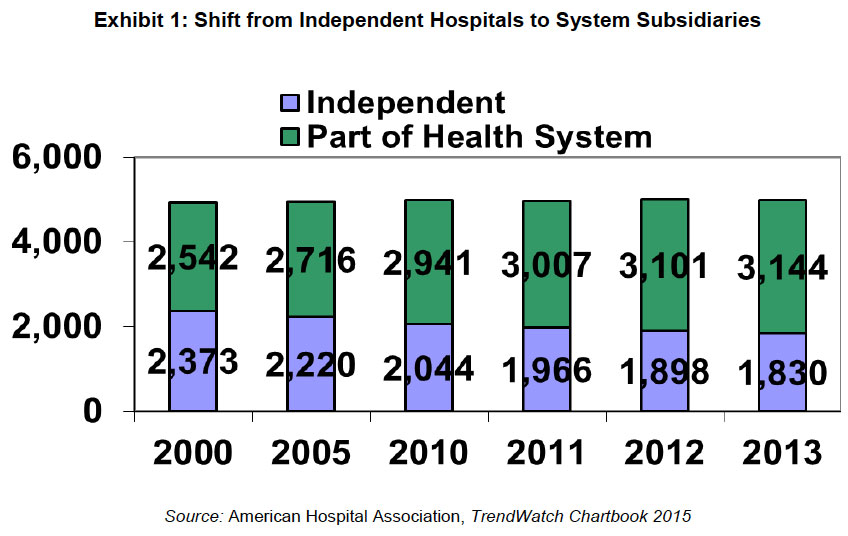

As shown in Exhibit 1, between 2000 and 2013, the number of community hospitals belonging to health systems increased by 602 hospitals, from 52 percent of all community hospitals to 63 percent.1 There are many reasons why independent hospitals (and also small systems) join larger systems, chiefly for:

- Access to capital

- Economies of scale

- Clinical integration and/or desire to become part of an accountable care organization (ACO)

- Affiliation with a critical mass of primary care physicians across a broad geography

- Drive toward clinical excellence and value (e.g., superior outcomes at a lower cost)

- Access to infrastructure to manage population health

Importantly, if a hospital is seeking access to capital through a merger or joining the system, the larger system/capital partner will require that it have so-called reserved powers—or the right to approve core board decisions—over the subsidiary. This is a practical reality: a health system/partner does not “give” money to a community hospital; that is the role for a philanthropist. The partnership trade-off is simple to understand, but in practice can cause tension. In return for the financial and other benefits of becoming a member of a system, once a hospital decides to give up its independence, its board operates under the governance control of the system or parent organization board.

Changing Governance Roles as Part of a Health System

In the evolution of health system governance, many systems started as parent “holding company” models with multi-tiered governance structures. Hospital boards operated within a governance “authorities matrix” that outlined roles and responsibilities of management and boards at all tiers. In larger systems, these tiers may include the system board, regional boards, local hospital boards, and even boards of subsidiaries of the hospitals. As reported in the Governance Institute’s 2015 biennial survey, there has been a consistent trend away from subsidiary boards holding full responsibility toward shared responsibility between subsidiary and system boards.2 Additionally, many systems have sought to streamline governance to no more than a two-tiered structure or to a single unified board structure. Compared to the roles the board in an independent hospital played, these new subsidiary boards, if maintained, play very different, but still important, roles in a world increasingly focused on addressing community needs, population health management, and community partnerships.

It is important for subsidiary boards to recognize that they exist not just to ensure community input, but to facilitate the implementation of the policies established by the system board. Essentially, such subsidiary boards are an extension of the system board and its work.

Let’s compare the roles common to a subsidiary board to those of an independent board around the three key roles previously outlined.

- Subsidiary board’s role in mission and strategic direction. Best governance practices nationwide call for system boards to establish a system-wide mission and strategic direction. This results in one, unified system-wide vision statement, set of goals, and goal-related metrics that become the vision, goals, and metrics of each subsidiary (albeit with differing expectations or targets by entity). The subsidiary boards’ role is to support the system board by “advancing” or “furthering” the system’s strategic direction in the local community or region. Often, subsidiary boards are called upon to evaluate and address community health needs, identify unique market dynamics, and further local partnerships as they “advance” the system’s strategic direction.

- Subsidiary board’s role in setting policy. Best practices on policy-making suggest that most policies will be recommended to the system board by its own committees/system management, then approved (“set”) by the system board. For example, the system board establishes financial policies, sets the system annual operating and capital budgets, and articulates system-wide quality metrics. Most HR policies also are set by the system board. In more well-developed systems, system management then establishes realistic and achievable targets for each subsidiary. Most of these policies and targets are not set, or even recommended, independently by the subsidiary board.

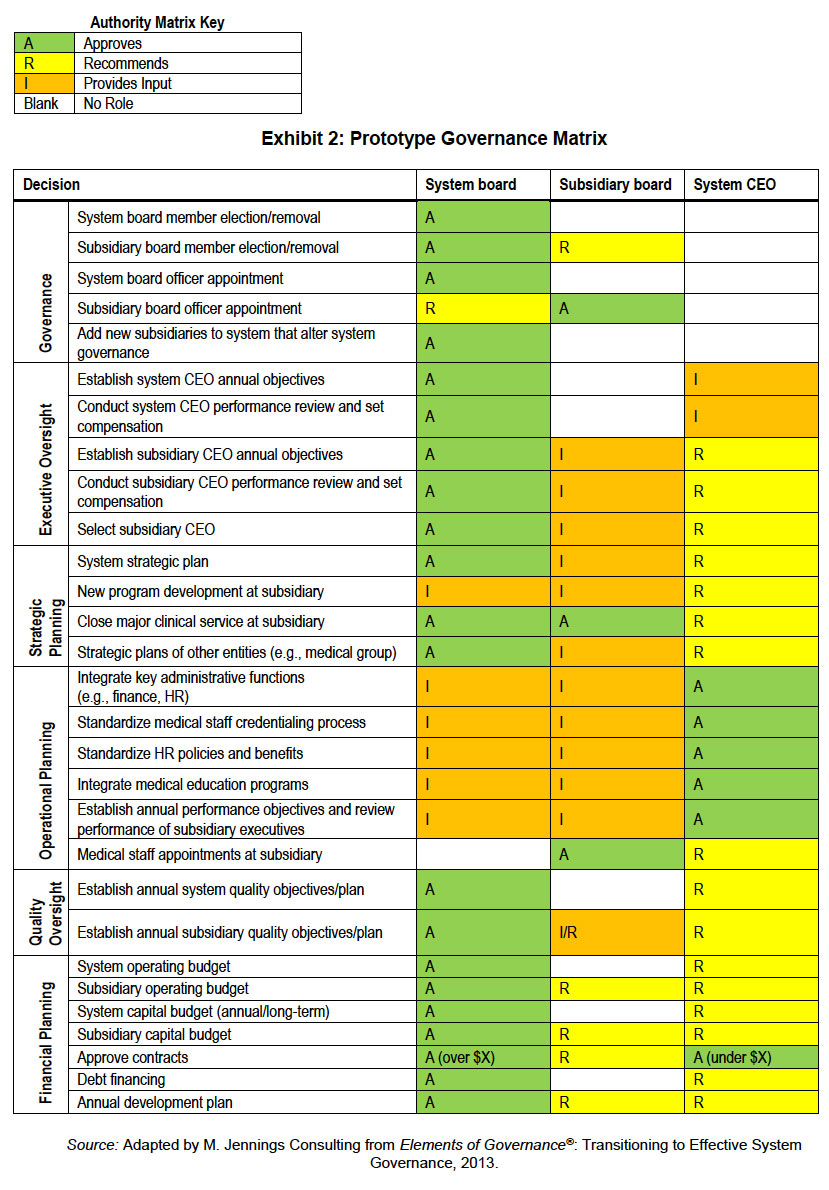

Some systems still desire that subsidiary boards “recommend” their operating and capital budgets, but this is generally a pro forma activity since the local annual budget targets are set by a system finance team in discussions with local management. The same is true in quality, HR, and other arenas. Exhibit 2 presents a prototype governance matrix where, as indicated, the subsidiary board has limited final authorities; its most common role is, at best, to provide input into policy making. - The subsidiary board’s role in oversight. Subsidiary board members still retain a significant role in oversight at the local level, albeit in conjunction with management oversight by system executives. For example, the chief financial officer of the subsidiary hospital typically will hear from his system counterpart if performance is below budget and be asked for his/her corrective action plan—often before the local board has convened to review operating performance.

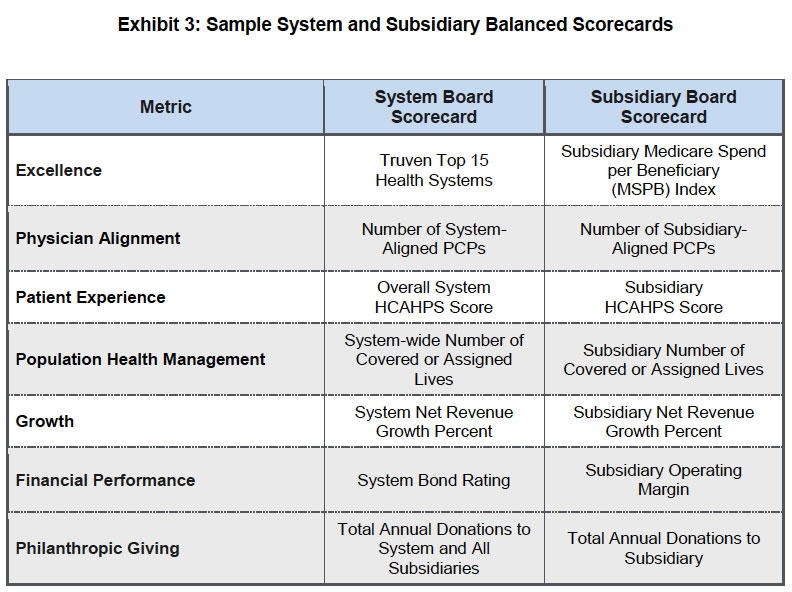

Moving into the future, the subsidiary board should focus on oversight that furthers the system’s overall strategic plan and address local needs. Often, this is accomplished by focusing on a limited list of strategic metrics (a strategic “balanced scorecard”) identified by the system that are essential to long-term success. Exhibit 3 shows an example of a balanced scorecard for a system board as well as the counterpart subsidiary board. In the event that performance is lagging against a system-established scorecard metric, the subsidiary board should ask management for a corrective action plan and monitor improvements to get back on track.

Why Maintain a Local (Subsidiary) Board?

Even though formal authority is vested in the parent board, local hospital boards can add value to the local healthcare organization and the community it serves. The local board and its CEO know the local market, community needs, and special circumstances far better than a corporate board or system managers overseeing a broad geography. Therefore, the local board can add value in the areas of identifying community partnerships that could benefit the hospital, focusing on enhancing the community’s health versus treating illness, monitoring quality of care to ensure that local residents are obtaining the highest possible quality and service, supporting strong ties to the community, and encouraging philanthropic support. In particular, subsidiary board members, through their key roles in credentialing of health professionals, can be extremely important partners in driving quality initiatives and value-based performance. The subsidiary board should also participate in local CEO goal-setting and evaluation. Importantly, if subsidiary boards don’t have meaningful responsibilities, they won’t be able to attract and retain talented directors who could put their volunteer efforts to work elsewhere.

Committees at Subsidiary Level

Compared with independent hospital boards, subsidiary boards have less need for local committees. Financial performance, for example, is overseen at the system level by system subject matter experts and the system board. Most subsidiary boards do maintain a local board committee focused on quality and value, which includes credentialing of medical professionals, and a local governance committee, focused on governance competencies, board self-assessment, recruitment, and board orientation and education. Recently, some subsidiary boards have moved to using the board-as-a-whole to oversee quality since “quality care is delivered locally” and oversight in this area is a key responsibility.

Conclusion

Emerging best practices in healthcare governance call for value-added, non-duplicative work and input at each level of governance. The “right” balance between system board and subsidiary board roles varies from system to system. Regardless of the particular approach, subsidiary boards have less authority and play different, but still important, roles compared to board roles at an independent hospital. More focus on overseeing organizational performance in quality and service; less on financial oversight. More focus on population health; less focus on this month’s patient volumes. More focus on delivering value to the community; less focus on how our negotiations with Blue Cross are going. More need for members who have experience in quality improvement or leading an organization in an industry going through dynamic transformation; less need for those whose primary competencies are in understanding financial statements.

Ensuring role clarity is essential to reducing confusion and frustration. Identifying the kinds of skills, experiences, and core competencies needed on the subsidiary board and intentionally recruiting for these new competencies is essential. Attracting committed area residents to serve on the board of a hospital used by their friends, neighbors, and families can still be accretive to the hospital’s long-term success.

Additional Resources

The Governance Institute has several resources for helping you clarify system versus subsidiary board roles. Below are a few we suggest:

- Transitioning to Effective System Governance (Elements of Governance®, 2013)

- System–Subsidiary Board Relations in an Era of Reform: Best Practices in Managing the Evolution to and Maintaining “Systemness” (White Paper, Fall 2011)

- Governing the 21st Century Health System: Creating the Right Structures, Policies, and Processes to Meet Current and Future Challenges and Opportunities (White Paper, Fall 2013)

- “Competency-Based Board Recruitment: How to Get the Right People on the Board” (Governance Notes, February 2015)

The Governance Institute thanks Marian C. Jennings, President, M. Jennings Consulting, for contributing this article. She can be reached at mjennings@mjenningsconsulting.com.

Governance Notes – October 2014

Marian C. Jennings, President – M. Jennings Consulting, Inc.

› Download PDF

1 American Hospital Association, TrendWatch Chartbook 2015.

2 Kathryn C. Peisert, 21st-Century Care Delivery: Governing in the New Healthcare Industry, The Governance Institute’s 2015 Biennial Survey of Hospitals and Healthcare Systems.