The Right Fit: Stand-Alones and Small Systems Must Get the Questions Right

When the U.S. Supreme Court upheld the Affordable Care Act (ACA) in June 2012, leaders across the health care industry saw that reform not only was here to stay, but it would be accompanied by a momentous shift away from payment for discrete episodes of care (fee-for-service) toward full management of a population’s lifelong health (global payment).

The change in payment philosophy will fundamentally change the structure of the U.S. health care system. It will move the hospital out of the center of the health care universe and demand collaboration across the continuum and the ability to serve and manage a critical mass of people.

For those who have been in the health care industry since the merger-and-acquisition boom of the early 1990s, the scenario may seem familiar. According to Irvin Levin & Associates, there were 94 hospital merger-and-acquisition deals in 2012, more than the industry has seen in a decade. It seems that not a week goes by without another article in the press on hospital mergers.

As in the ’90s, stand-alone nonprofit hospitals and smaller systems now are merging, joining existing larger systems or seeking partners to meet the demands of a changing market. Specific objectives of such partnerships often include: to achieve economies of scale; to build the primary care, IT, and contracting infrastructures to manage population health; to develop clinical best practices that result in better outcomes at a lower cost; to offer a geographically distributed, comprehensive, integrated continuum to create a network attractive to payers developing accountable care organizations (ACOs) or to become ACOs themselves; and/or to partner with a health plan or attain an insurance license to offer their own health plan.

Our experience is that the benefits outlined above — often the ostensible reasons for affiliation — can be achieved via a carefully

constructed network without the hospital’s ceding full autonomy. However, underpinning many partnerships is the need to increase access

to capital. The only ways to do so are to:

- Attract a major benefactor who will essentially “give” you the capital you need.

- Dramatically and consistently improve financial performance to enhance your financial capability.

- Merge, be acquired, or form a “look-alike” integrated model such as a joint operating company (JOC). Although no two JOCs look exactly alike, typically the model merges health care operations, at least from the managerial and governance perspectives. For governance oversight, usually the two sponsoring entities — whether one or both are Catholic — appoint a board with the seats split 50-50 between them. Sponsorship of church assets remains with the original sponsors, who also retain a set of core reserved powers over the JOC board.

Of the three options, No. 1 and No. 2 maintain autonomy. However, counting on major philanthropic gifts to ensure independence is often unrealistic, and strengthening the balance sheet during challenging financial times may take a decade. Option No. 3 compromises an organization’s autonomy. Hence, many hospitals and small systems are reluctant to consider it proactively.

Compounding an already difficult decision about whether to stay independent, the concerns of independent Catholic hospitals and smaller health systems extend beyond the strategic and business considerations of their fellow not-for-profit organizations. For Catholic health sponsors and leaders, two key questions emerge:

- From a strategic/business perspective, can we thrive as an independent? If not, what are our options?

- If we do decide to merge or join a system, how will we protect our Catholic identity, heritage and mission?

This article explores the strategic and business considerations of various types of affiliation, with particular emphasis on the unique considerations for Catholic health ministries.

Don’t Skip The ‘Why’

First, leaders at any organization should ask themselves why they might seek a partnership or merger. Partnerships or mergers are not ends in themselves; they are means to an end. Being able to articulate clearly what your organization is trying to achieve over the next five years — and whether and how a partnership could help you achieve that end — is a critical first step. Unfortunately, it is a step too often skipped as the discussion prematurely focuses on legal structures, organizational charts and lists of reserved powers.

As basic as it sounds, it is helpful for the board and senior leaders to answer three key questions before even considering a potential partnership:

- What do we want from the partnership?

- What do we need from the partnership? (In other words, we would not pursue this relationship unless it offered us the following…)

- What do we bring of value to the partnership — and what would we like our future partner to recognize as the value that we bring?

The most successful partnerships flow from already established strategy. As a recent report from the international management consulting firm Booz & Company states:

“In a[n …] analysis of more than 200 deals among hospitals and health systems between 1994 and 2011, we discovered that more than half of them did not result in higher performance — and 18 percent actually sank as their margins turned negative. The greatest returns came from deals in which hospitals pursued a consistent approach to acquisitions that was tightly aligned with the strategic need for capabilities or scale. These deals helped hospitals create more attractive networks for employers, achieve the right scale to support a specialized hub, or create a more integrated continuum of care. In short, the intent of a deal is essential to its ability to create value.” [Emphasis added.]

Creating a clinically integrated network or a network of hospitals, physicians and other continuum providers that will be capable of assuming and managing population health risk is one of the areas of greatest interest for hospitals of all sizes. Most realize it would be impractical and unaffordable as a solo institution to build the infrastructure needed to become an effective ACO or to manage risk payments. A Jan. 23, 2013, Wall Street Journal article on ACOs quotes Tom Scully, former Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services administrator, who said: “The start-up cost of a real ACO is probably $30 million and up in a midsize market — and doctors

don’t have that capital. So hospitals are pitching that they will be ACOs, and buying up practices.”3

One such partnership is MissionPoint Health Partners of Nashville, Tenn., a nonprofit, clinically integrated network started in January 2012 by Saint Thomas Health, part of Ascension Health. The network’s stated goal is to “provide quality, patient-focused care while also reducing overall healthcare costs and rewarding providers for delivering the highest quality of care” as an ACO.4 In July 2012, it became a member of Medicare’s Shared Savings Program. In just over a year of operation, the network has grown to 1,500 physicians; membership has increased from 10,000 to 50,000; and MissionPoint saved 12 percent in cost on its first 15,000 members. In addition, MissionPoint has signed an agreement with Blue Cross Blue Shield of Tennessee and has had another smaller system, Capella Healthcare of Franklin, Tenn., join the network to share quality data and integrate with MissionPoint’s IT infrastructure.

In this example, as in many successful partnerships, network formation is a means to a specific strategic end, not a strategy in itself. Network participants cede some control to the network to obtain the benefits, but they do not give up overall autonomy, nor do they attempt full merger.

Range of Partnership Options

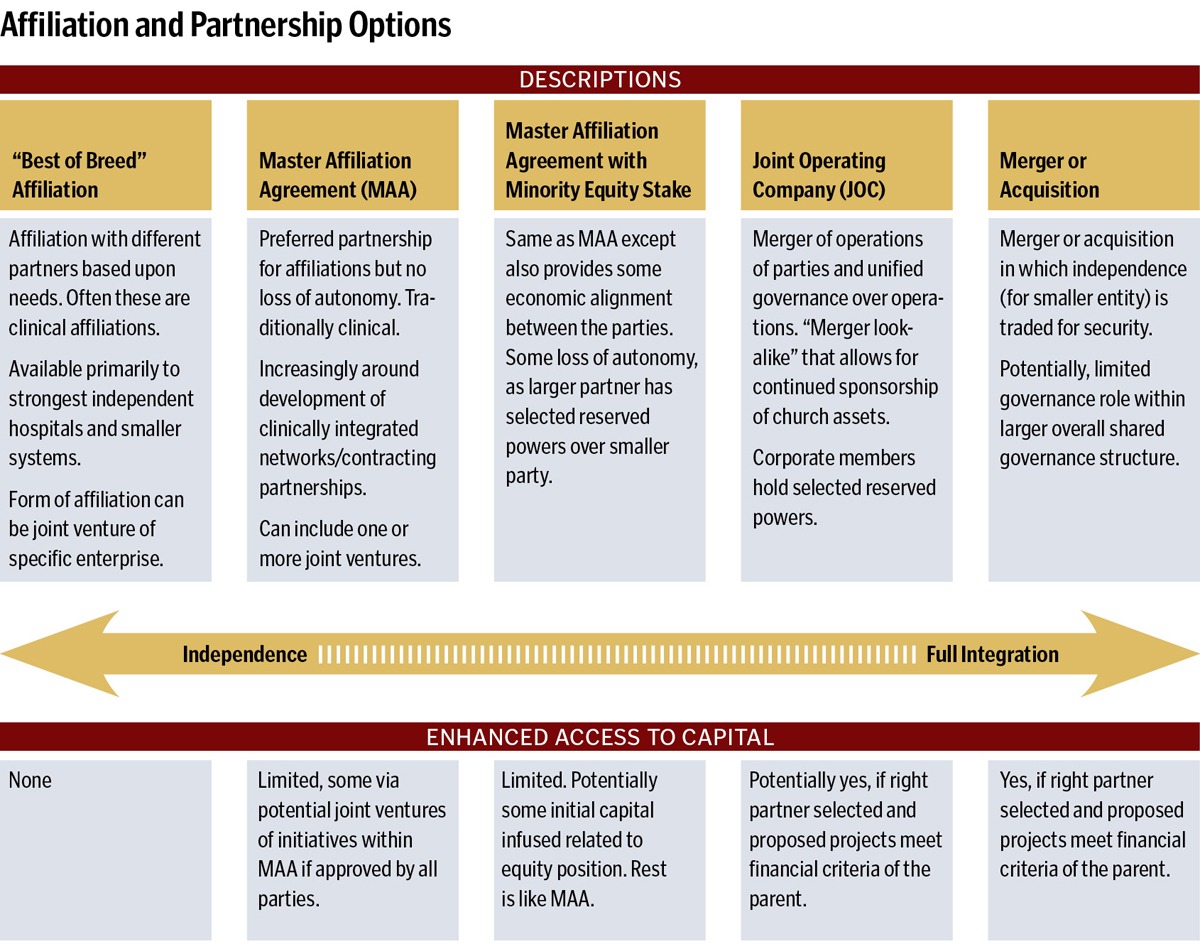

Many view partnership as an either/or choice — either we remain independent or we merge — though that’s not exactly the case. There are ways to affiliate in not-for-profit health care today, especially for stronger hospitals and small systems, which still allow different degrees of independence.

Make no mistake, however: if access to capital is a primary objective, you must look at the fully integrated partnership models. In a 2012 white paper, the Governance Institute described the trade-off between independence and becoming a member of an integrated health system in this way:

“With the integrated system approach, all local sub-systems operate from a unified and common strategic plan, clinical model, financing structure, and physician/provider services method. With this approach, it is not reasonable to permit unrestricted ‘local autonomy.’ Local boards may remain in place, but localized, decision-making freedoms are exchanged for a unified brand and consistency of clinical care programming, clinical quality, patient safety standards, and third-party contracting methods and strategies.” [Emphasis added.]

For Catholic hospitals and smaller systems, there are unique considerations that must be incorporated into any decision about remaining independent. The following questions may be difficult to pose, but it is crucial to reflect upon them sooner rather than later:

- Do you have a sustainable sponsorship model for the future? How many religious sisters will be interested in and able to exercise their sponsorship responsibilities in 2018? In 2023? Many of the larger Catholic systems formed in the 1990s were created specifically to design an enduring sponsorship model that anticipated an increased role for the laity in sponsorship. If you remain independent, what sponsorship model will be in place to ensuring the ongoing presence of a vibrant Catholic health ministry — and are you proactively establishing this model today?

- As you begin to forge or participate in regional networks — for example, to participate in a clinically integrated network with secular partners — will you be able to maintain your Catholic identity, ensure that Catholic values are respected, and influence the network as a whole around principles intrinsic to the ministry?

- Could being a member of a larger Catholic system with a well-developed approach to mission integration and more experience in forming or participating in such regional networks strengthen your negotiating position or enhance your ability to influence the regional network, once established?

- How will the decisions you make today contribute to a vibrant Catholic health ministry in 10 years? In 20 years? How would retaining independence, partnering locally or regionally with non-Catholic organizations or partnering regionally or nationally with larger Catholic systems further the overall mission and ministry of the church? Which options best perpetuate your founders’ mission?

Risks of Partnering

Just as with any major decisions that have long-term implications, there are major risks related to partnership. These risks fall into four broad categories:

- Cultural or selection risks: More mergers and partnerships fail due to cultural incompatibility than any other reason. Often a partner is selected for all the wrong reasons (e.g., “they are not that different from us and won’t threaten the status quo”). It is essential to select a trustworthy partner with a compatible mission and values, a commitment to the same goals as yours and a proven track record of effective implementation.

- Lack of common vision: Clearly identifying a shared vision for the partnership is essential. Be as specific as possible on what the vision really means to all parties. We have found that it is immensely valuable to state desired five-year objectives as clear, quantifiable “destination metrics” where possible.

- “All we really wanted was money”: Any relationship based exclusively or primarily on money — whether a marriage, an employer-employee relationship or organizational partnership — is a bad relationship. If you only want money, you should go to a bank, not partner with a health care organization. To access capital through a partnership, you must be willing to cede autonomy and control. There is no such thing as a no-strings-attached partnership in which substantial capital flows from one party to another.

- The structure is too weak to deliver on the promise: The old adage is, “form follows function,” but in the case of partnerships, function can be frustrated by the wrong form or structure. It can be very tempting to compromise on the structure to get the deal done. However, beware of compromises that generate ambiguity around decision rights — that is, the how, where and who of decision-making.

Ultimately, an independent Catholic organization’s decision whether to merge or form another sort of partnership should flow from the organization’s vision, strategic plan and financial capability to invest as needed to transform delivery as required by health reform. Moreover, any organization — especially those with the unique and important Catholic heritage and commitments — must take into account a potential partner’s history, culture and mission to determine whether these will facilitate a successful partnership.

Finally, independent organizations wishing to partner must recognize that stronger, more durable forms of alignment, though potentially advantageous in the long run, will result in at least some loss of autonomy in decision-making. Careful consideration of these factors will help your organization make the difficult decision whether and when to partner in our challenging and changing health care environment.

MARIAN C. JENNINGS is founder and president of M. Jennings Consulting, a health care management consulting firm based in Malvern, Pa. She has worked for three decades with Catholic hospitals and systems across the country and was very involved as a facilitator in The New Covenant collaboration efforts in the 1990s, which were sponsored in part by the Catholic Health Association.

Notes

- Irving Levin Associates, Inc., “M&A Deal Volume for 2011 and 2012,” www.levinassociates.com/pr2013/pr1301mamyearend (accessed April 29, 2013).

- Booz & Company, “2013 Payor/Provider Industry Perspective,” (Dec. 13, 2012) www.booz.com/global/home/what-wethink/industry-perspectives/display/2013-healthcare-payor-provider-industry-perspective?pg=1 (accessed April 29, 2013).

- Heather Punke, “Growing and Engaging an Accountable Care Patient Base: Q&A with MissionPoint Health Partners’ CEO Jason Dinger,” Becker’s Hospital Review (March 27, 2013) www.beckershospitalreview.com/accountable-care-organizations/growingand-engaging-an-accountable-care-patient-base-qaa-with-missionpoint-health-partners-ceo-jason-dinger.html (accessed April 29, 2013).

- Anna Wilde Mathews, “Can Accountable-Care Organizations Improve Health Care While Reducing Costs?” The Wall Street Journal, Jan. 23, 2012 http://online.wsj.com/article/SB10001424052970204720204577128901714576054.html (accessed April 29, 2013).

- MissionPoint Health Network website, www.missionpointhealth.com.

- Daniel K. Zismer and Frank B. Cerra, High-Functioning, Integrated Health Systems: Governing a “Learning

Organization,” white paper (San Diego: The Governance Institute, Summer 2012).

Is It Realistic to Think You Can Remain Independent?

In today’s rapidly changing, even hostile environment, it is important that a hospital or smaller system have a realistic view of its ability to remain independent over the next five years.

From our experience, hospitals and smaller systems with the greatest likelihood of sustaining themselves as vital, independent hospitals or systems demonstrate most or all of the following characteristics (in priority order). If your organization does not demonstrate most of these characteristics today, time is of the essence in considering options. Even the strongest Catholic health systems do not have the financial wherewithal to absorb every financially distressed Catholic hospital seeking a partner.1

- Strong financial performance; financial ratios consistent with at least an A+ bond rating and sufficient access to capital for the next five years

- Larger and stronger player in its market/region or sole community provider

- Well-aligned or employed primary care physician base that is sufficient to support 70 percent or more of its overall activity

- Demonstrated capability to manage population health or achieve maximum incentives under existing value-based payment or global payment contracts

- Sufficient population base to support population health management infrastructure

- Consistently named among Truven Health Analytics’ 100 Top Hospitals or on Truven’s 15 Top Health Systems list

- Strong value position: relative low cost position; top quartile performance on clinical outcomes and satisfaction

- Strong, positive brand name; consumers in its market rate it as No. 1 choice

- Strong payer relationships, payer has reached out to establish innovative contracts (e.g., value-based payment)

- Geographically distributed outpatient centers/primary care sites in place

Catholic Health Association, Health Progress – July/August 2013

Marian C. Jennings, President – M. Jennings Consulting, Inc.

› Download PDF

1 Marian C. Jennings, “Access to Capital: The Gold Rush is On,” in Futurescan 2012; Healthcare Trends and Implications

2012-2017 (Chicago: Health Administration Press, 2011).