Using Metrics to Evaluate Your Strategic Plan

“What you measure is what you get.” This old adage is extremely apt in today’s health care organization. Interest among corporations of all types in developing clear strategic metrics or “measures of strategic success” has increased dramatically over the past several years. This is due in large part to the work of Robert Kaplan and David Norton, whose many articles and books, especially their 1996 book, Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action1, established a practical framework now extensively used across many industries. This framework and many of its underlying concepts can be successfully adapted to the non‐profit hospital and health system environment.

What are Strategic Metrics?

Strategic metrics – or measures of success – are benchmarks used to create clarity around the desired outcomes of the strategic plan and to assess organizational progress toward achievement of the organization’s strategic intent (Mission and Vision) and its specific goals and strategies. Strategic metrics include two components:

- A measure, or criterion used as the basis for evaluating success (for example, market share as a measure of growth); and

- A target, or specific value associated with a measure, that the organizations wishes to achieve (for example, inpatient market share will increase by five points by 2009).

Benefits of Using Strategic Metrics

Strategic metrics focus the organization on the desired outcomes of its plan rather than simply the process (strategies, actions, and tactics) that will be employed to achieve the organization’s Mission and Vision. This one attribute makes strategic metrics immensely valuable.

Using clear strategic metrics offers several benefits to hospitals and health systems:

- Strategic metrics add substance to strategy statements and help people at all levels of the organization to visualize “what we are really trying to achieve.” They can serve as a goal line toward which a team can coalesce.

- Strategic metrics – often stated as objectives for five years out – allow for better monitoring of annual progress toward the desired outcome. Most organizations establish both long‐term metrics and expected outcomes for the current fiscal year. These current year strategic metrics can and should dovetail with management performance incentive plans.

- Strategic metrics create “balance” between the organization’s financial objectives and other indicators of success. In fact, this is one of the primary concepts explicated by Kaplan and Norton in their landmark book. All organizations, including non‐profits, have very clear financial indicators (metrics) which are reviewed routinely by senior management and the Board. Kaplan and Norton2 advocate establishing similarly clear‐cut measures of success around market position, internal business processes, and innovation – thus creating a more “balanced” scorecard.

As it turns out, this is especially important in not‐for‐profit organizations, since financial achievement on its own (e.g., providing a return to shareholders) is not the primary goal, as it is in the corporate world. Ironically, many hospitals and systems lack this kind of balanced review of their accomplishments and – in the absence of a more balance approach – could be perceived by physicians, employees, and community members to be more interested in strong financial performance than in quality, employee satisfaction, image, innovation, and other dimensions of performance.

The Board should be actively involved in developing and approving such measures – whereas the specific strategies, actions, and tactics should be left to management.

Defining Measures

To be effective, a Balanced Scorecard should include a limited number of key measures – ideally a dozen or so. The measures should focus on key areas of importance and be as specific as possible. In addition, the metrics should be both conceptually appealing and easily

quantifiable. This latter point is especially important in health care, where the most desired information (e.g., quality of our obstetrical services vs. area competitors) often cannot be obtained or will be available only with a lag of several years.

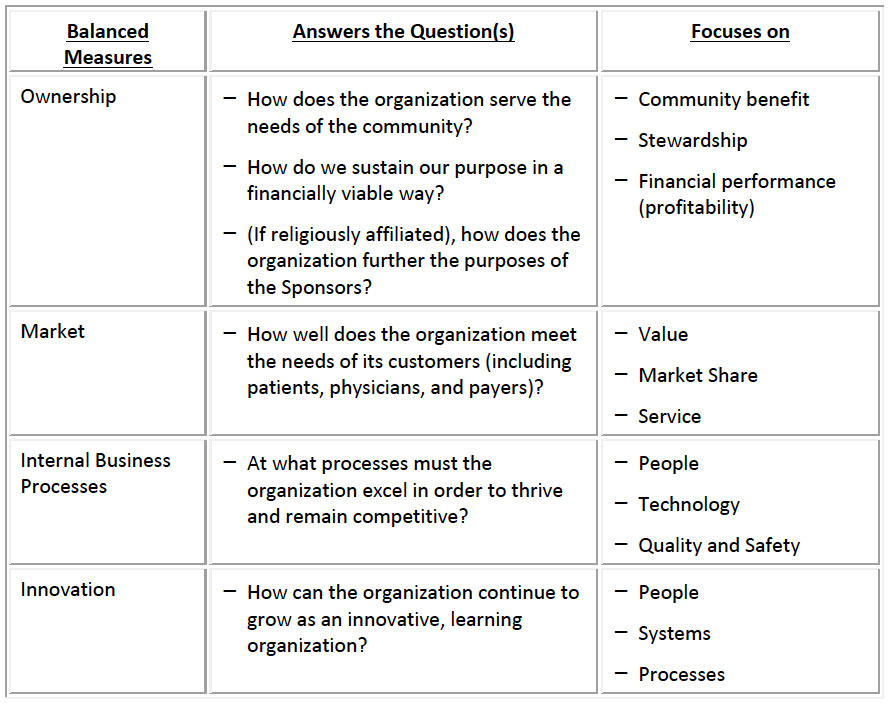

The following framework, adapted from the work of Kaplan and Norton, can be used to define a robust set of balanced measures for not‐for‐profit hospitals and systems:

Setting Targets

Once a set of measures has been selected by senior management and the Board, how should you define the appropriate targets for the end of the planning cycle? The Board’s role in establishing targets differs from its role in establishing the measures themselves. Specifically, the Board should be more active in determining measures than in developing specific targets. The targets are best developed by a process that engages senior and mid‐level managers, as well as physician leaders. By doing this, the organization highlights the importance of the metrics process, brings people to the table who have the experience to appreciate “what it will take” to achieve the targets, and facilitates buy‐in to the whole Balanced Scorecard approach.

Once targets have been selected, it is our experience that targets are best expressed as a range of acceptable performance, rather than as one expected outcome; in other words as a “corridor” of expected performance rather than a “bulls‐eye.” In this way, the organization can reward those responsible when performance is above a pre‐defined level and implement corrective actions when performance fails to achieve the pre‐defined “lowest” acceptable level.

Common pitfalls in establishing appropriate targets include: targets that are overconfident or assume a turnaround that is unfounded based upon the core strategies (“superman syndrome”); targets that are overly conservative (“just to be on the safe side – and to protect our incentive payments”); and targets that are limited based upon past performance (“the plan really won’t make a difference).3

Caveats

If your organization is establishing a Balanced Scorecard for the first time, you should prepare yourself for an iterative process of learning which may take several years. Few, if any, organizations actually design an ideal set in their first attempt. If it usually only after the first reporting cycle that hospitals/systems realize that:

- Some of their measures are irrelevant or inappropriate. (“We achieved the target, but we really didn’t achieve what we wanted to.”)

- There are too many measures and targets. (“We achieved 20 out of 25 targets – but we don’t feel successful since the five we did not achieve were the most important.”).

- Some of their targets are too lofty. (“It was unrealistic to expect this kind of performance so quickly.”)

- Despite their best efforts, come of their targets are not measurable.

- There is confusion about how the Balanced Scorecard meshes with a broader set of management “dashboard” metrics which monitor operational performance. Try to keep the Balanced Scorecard aligned with strategic goals rather than at the detail associated with operational strategies, policies, and procedures. However, make sure that there is congruence between the strategic metrics and those measures routinely reviewed as part of management’s operational oversight.

Don’t let these potential pitfalls deter you or get discouraged if any or all of the above occur in your organization. The metrics‐based Balanced Scorecard, like any approach that tries to focus the perspectives of many people simultaneously, takes a great deal of effort and persistence. However, using the Balanced Scorecard can be extremely productive if pursued with a willingness to learn and adapt the tool, based upon experience, and a belief that it will, in fact, move the organization closer over time to accomplishing its Mission and Vision.

The Governance Institute, BoardRoom Press – December 2017

Marian C. Jennings, President – M. Jennings Consulting, Inc.

› Download PDF

1 Kaplan and Norton, The Balanced Scorecard: Translating Strategy into Action. Boston, MA: Harvard Business School Press, 1996

2 Ibid

3 Hammond, Keeney and Raiffa, “The Hidden Traps in Decision Making.” Boston, MA: Harvard Business Review, September-October 1998.